Indonesia's Empty Ambassador Post in Washington: A Blunder Amid Trump's Reciprocal Tariffs

When United States President Donald Trump proclaimed America’s Liberation Day on 2 April 2025, Indonesia could only stand agape. The country failed to respond promptly, let alone anticipate the move. And little wonder — the Indonesian ambassador’s post in Washington had been vacant for nearly two years. Yet Trump had repeatedly trumpeted Liberation Day since his campaign trail. When he was inaugurated as US President on 20 January 2025, Trump also heralded the imposition of reciprocal tariffs on America’s trading partners. Roughly a week before Liberation Day was launched, US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent revealed that Washington had drawn up a “Dirty 15” list — referring to the countries contributing the largest deficits to the US trade balance. Bessent even confirmed that Trump would proclaim Liberation Day on 2 April 2025. Simultaneously, the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) had already compiled a list of 21 countries to be targeted, including Indonesia.

Yet Indonesia responded poorly to these signals. Perhaps the government was overconfident that the US would not target Indonesia, and consequently failed to place a representative in Washington in a timely manner. The last person to occupy the post was Rosan Roeslani, who served as Indonesian Ambassador to the US from 25 October 2021 until 17 July 2023 under President Joko Widodo. Rosan was then appointed Deputy Minister for State-Owned Enterprises on 17 July 2023, before becoming Minister of Investment and Head of the Investment Coordinating Board (BKPM) on 17 August 2024. Under President Prabowo Subianto, Rosan joined the Merah Putih Cabinet, being inaugurated as Minister of Investment and Downstreaming cum Head of BKPM on 28 October 2024.

Without an ambassador in the US, Indonesia’s trade diplomacy with Washington has lacked intensity. To date, Indonesia has no Ambassador to the US to replace Rosan. Prabowo inaugurated 31 Indonesian ambassadors for other countries on 23 March 2025, yet not a single one was posted to the United States. Whatever the government’s reasons for leaving the post vacant for nearly two years, the US remains Indonesia’s second-largest trading partner after China. In 2024, for instance, the US contributed a non-oil and gas trade surplus of US$16.08 billion out of Indonesia’s total trade surplus of US$31.04 billion with all its partners.

The vacancy represents a blunder for Indonesia. Like a football team without a goalkeeper, Indonesia had no one to fend off America’s attacks. Without its ambassador, Indonesia lacked a figure who could directly lobby Washington as Trump began proclaiming Liberation Day. Even a week before the reciprocal tariffs were launched, Indonesia still had no goalkeeper in place.

The vacancy also left other matters unattended, including the Generalised System of Preferences (GSP) — the granting of duty reductions of up to zero per cent on various Indonesian export commodities entering the US market. In 2020, the US suspended the review and extension of the GSP. To this day, Washington has not provided certainty on the legal status or timeline for extending these tariff privileges. Indonesia had the opportunity to lobby the US intensively on this matter, but that opportunity was squandered by the absence of an ambassador for nearly two years. By the time Trump announced reciprocal tariffs, Indonesia was only just planning to send a special delegation.

Nevertheless, though the damage is done, Indonesia still has opportunities to lobby and negotiate with the US.

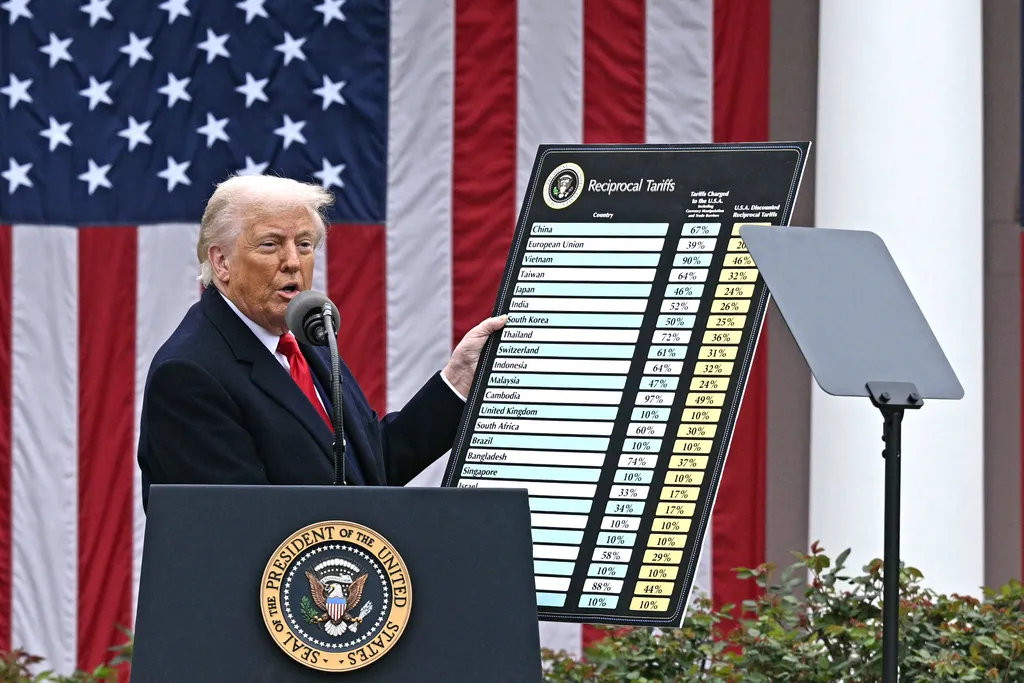

Trump’s “Sacred Document”

The Indonesian government must move swiftly to appoint an ambassador to the US and form a special delegation to respond to Trump’s reciprocal tariffs. The US began enforcing these tariffs on 9 April 2025, meaning Indonesian products entering the US would face a 32 per cent import duty from that date onwards.

The tariff policy has already led to the postponement of orders by US importers. In Bandung, West Java, for example, plans to export Wanoja arabica coffee to the United States were temporarily suspended. The Indonesian Furniture and Handicraft Industry Association (HIMKI) also reported that US furniture import orders had been put on hold.

In future negotiations with the US, Indonesia must also challenge the calculation methodology behind the reciprocal tariffs. Many observers consider this calculation to deviate from the World Trade Organisation’s (WTO) principles of fairness and reasonableness under the most favoured nation (MFN) framework.

Furthermore, Indonesia should use Trump’s own “sacred document” — the 2025 National Trade Estimates (NTE) report published by the USTR. In this report, the USTR details various Indonesian policies deemed detrimental to US interests, covering both tariff and non-tariff barriers. The US considers Indonesia’s import approval process overly cumbersome, requiring clearance from multiple ministries and agencies. For food imports, for instance, approval requires recommendations from relevant ministries and must be based on commodity balance sheets to determine import quotas. The US also noted that Indonesia restricts feed corn imports by limiting import rights to Perum Bulog, and highlighted the provision of subsidised loan interest rates to micro, small, and medium enterprises.

The US also raised concerns about Indonesia’s technical barriers to trade (TBT), including the complexity of meeting local content requirements (TKDN) and halal certification requirements. However, the US itself imposes tariff and non-tariff policies on Indonesia. Indeed, the Institute for Development of Economics and Finance (Indef) notes that US non-tariff policies are actually more numerous than Indonesia’s. This is indicated by the number of TBT and sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures — typically comprising labelling, certification, product standards, and health and environmental protections. In 2024, the US had implemented 495 TBT and SPS measures, compared with just 32 for Indonesia.

The Indonesian government plans to pursue diplomacy in response to the reciprocal tariffs. It has also prepared measures to address the various concerns raised by the US in the NTE 2025, including deregulation — simplifying and removing regulations that hinder trade, particularly non-tariff policies. In pursuing this deregulation, the government must be careful not to commit another blunder that harms domestic industry.

The question remains: will the government’s response amount to a mere “yes, sir” to Trump, or will it also fight for fairness in the national interest?